The Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD) is the national standard for all traffic control devices used in the United States on roads open to public travel.[i] There are two groups of target road users: 1) vehicle operators, including cyclists, and 2) pedestrians. The MUTCD has been owned and administered by the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) since 1971 with primary objectives to:[ii]

- Provide national uniformity in traffic control devices

- Serve as the key traffic/transportation engineering reference document

- Stand as the only transportation engineering document that is identified in federal code as the national standard

- Serve as the only document that requires compliance of federal and state law on all roads open to public travel regardless of classification or ownership.

Compliance with the MUTCD has multiple motivations, for example:[iii]

- Promotion of roadway safety

- Mobility (efficiency) of roadway users

- Meeting the needs of specific road user groups

- Achieving consistency with national and/or state traffic control device practices

- Reducing exposure to tort liability lawsuits

- Avoiding potential losses of federal transportation funding

Section 1A.02 Principles of Traffic Control Devices

Traffic control devices are all signs, signals, and/or markings that use colors, shapes, symbols, words, and/or sounds for the primary purpose of communicating a regulatory, warning, or guidance message to road users on a highway, pedestrian facility, bikeway, pathway, or private road open to public travel.[iv] Other roadway elements like curbs and speed humps, or operational devices like in-vehicle electronics and roadway lighting are not traffic control devices.

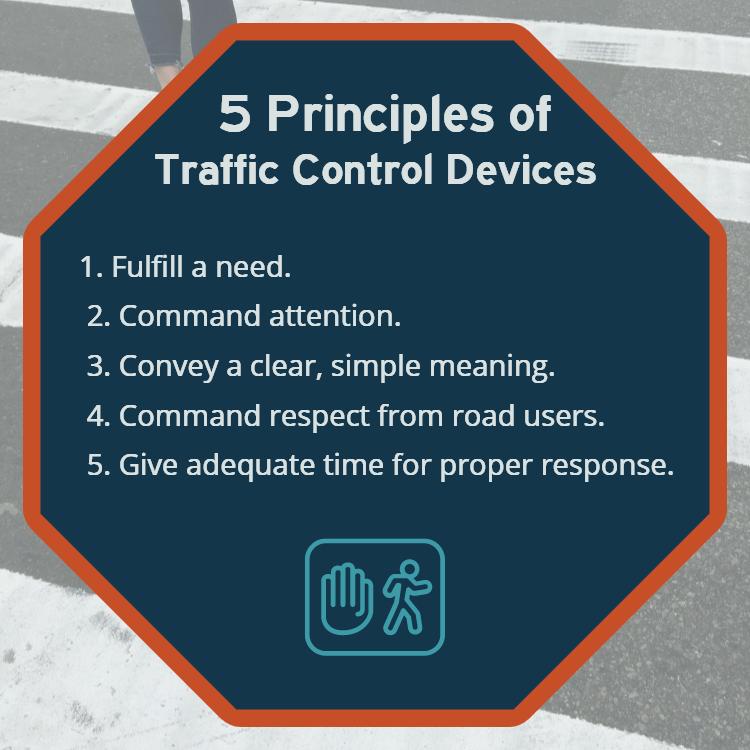

To be effective, a traffic control device should meet five basic requirements:

Needs and Challenges of the MUTCD

The MUTCD is a challenging document to navigate, read, and apply. Notably, it is not intended to be an education document and is written with the assumption that users have the appropriate experience and/or engineering expertise to interpret its guidelines and standards.[v] The MUTCD’s sections are organized by device type, making it especially difficult to coordinate recommendations for multiple devices at a single location. For example, an intersection that includes regulatory and warning signs, plus line markings and LED flashing beacons would require sourcing multiple sections throughout the manual to retrieve all pertinent information. Other challenges relating to the MUTCD include:[vi]

- High level of variability in field conditions

- Restricts flexibility of public agencies to operate roadways

- Wide range of roadway users

- Small agencies do not have traffic engineering staff for proper interpretation of the guidelines

- Difficult to predict the technological advancements over the next twenty years

- Balancing safety, mobility, and cost-effectiveness is difficult and may require decisions that do not optimize all three

- Many parts of the MUTCD do not list factors that should be considered for traffic control devices.

Amending the MUTCD

The MUTCD is a national standard and defined in the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR), so it can only be changed and revised through the federal rulemaking process. Most commonly, recommendations for revisions are submitted by the National Committee on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (NCUTCD), an organization dedicated to developing safe traffic control devices and practices. Comprising twenty-one sponsoring organizations and eight specialized technical committees, members are responsible for assessing the uniformity of traffic control on U.S. roadways.

Further, proposed MUTCD changes are supported by the FHWA and the NCUTCD based on scientific studies demonstrating benefits and effectiveness of the new or changed traffic control device. The MUTCD’s rulemaking process is grounded first and foremost in research and field studies, with a secondary focus on correcting errors, omissions, and technical inaccuracies. The last time the MUTCD was updated, it took two years from the Notice of Proposed Amendments (NPA) to the publication of the final rule. There were over 15,000 comments from 1,800 letters posted to the docket.

The MUTCD’s 2014 Vision and Strategic Plan stated that the form, format, and content of the MUTCD should change following the next rulemaking process to reflect an increasing diversity in practitioners and growing size and complexity of the organization’s mandate. Some of the changes may include:[vii]

- Smart search apps

- Reorganized content for improving flow

- Elimination of redundant and unnecessary language

- Cross-indexing

- Modular or tabular information formats

- More hotlinks and pop-ups

- Better position figures with associated text

- More summary table and figures to reduce text

- Reconfigure existing figures to better manage space

- Improved consistency

- Subheadings to help find information on a subtopic

Proposed Changes for the 11th Edition of the MUTCD

The MUTCD has not been amended since 2009. However, 2 revisions were incorporated in 2012. Initially, the FHWA had intended to publish a new version of the manual by 2016, but that deadline was not met. The manual is one of several roadway safety reference guides and is meant to supplement other publications like the Roadside Design Guide, Highway Safety Manual, and “Green Book,” which, when used collaboratively or in conjunction with the MUTCD, provide a more comprehensive, complete transportation directive.

Currently, the Federal Register notice describes 647 proposed changes to the MUTCD for the upcoming 11th edition. The rulemaking process has entered the NPA stage, and the comment period has been extended through May 14, 2021. Some noteworthy proposed amendments to the manual include:

- Clarification on the use of the 85th percentile speed. Currently, this guideline can be applied to all speed zones and roadway classifications, and states that speed limits be set within 5 mph of the 85th percentile of free-flowing traffic. The proposed amendment will make the 85th percentile speed only applicable to freeways, expressways, and rural highways. There will be new resources for establishing speed limits on other roadway classifications.

- Guidelines and standards for Rectangular Rapid-Flashing Beacons (RRFBs), which propose including an ‘audible information device’ that indicate when the yellow lights are flashing by producing a speech message that says, “Yellow lights are flashing” twice.

- New content to support the decision-making process for pedestrian crossings. The MUTCD and National Committee recommend using the FHWA’s Safe Transportation for Every Pedestrian (STEP) resources and guides.

- Standardized designs for speed feedback signs. The proposed standardized background color is yellow, not white. The sign message is a warning not a regulation, so for uniformity speed feedback signs should be yellow.

The MUTCD is 86 years old and has undergone many revisions and updates throughout its lifetime. Since its last edition, urban planning priorities have shifted, and transportation technologies have advanced in many exciting and unanticipated ways. Multiple stakeholders are rigorously participating in the rulemaking process while many others anxiously wait for the publication of the final rule. The docket is open for public comment until May 14, 2021.

Changes in the 11th Edition of the MUTCD

The 11th Edition of the MUTCD went into effect on January 18th, 2024. The FHWA gives all states two years from its effective date to adopt the new edition as their legal state standard.

Significant changes include:

- Clearer guidelines on speed limits (Section 2B.21). While it still references the 85th percentile speed rule, it advises against its use on urban and suburban main roads. Instead, speed limit decisions should take into account the road’s environment, characteristics, location, safety record, and past speed studies. An engineering study is still necessary to determine appropriate speed limits.

- RRFBs have officially replaced FHWA’s Interim Approval 21 in the MUTCD (Section 4L). RRFBs are approved for use at uncontrolled pedestrian, school, and trail crossings. Additionally, RRFBs can be deployed at crosswalks on free flow turn lanes and intersections with multiple crosswalks on the same approach. Like IA-21, RRFBs should flash in a wig-wag plus simultaneous (WW+S) pattern. When paired with an audible information device (AID), the speech message should say “Warning lights are flashing” twice upon activation rather than “Yellow lights are flashing.”

- Standardized designs for speed feedback signs (1D.05): Signs feature a yellow background color, as the sign message serves as a warning rather than a regulation.

Advocacy Makes Sense

Be a change-maker for safer streets. Designed for citizens, local groups, and officials advocating for safer roadways, this guide offers the latest standards for unsignalized pedestrian crossings in North America, plus tips for improving or building community crosswalks.