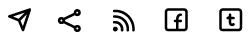

Every year, Smart Growth America’s Dangerous by Design report offers a sobering look at pedestrian safety in the United States. The numbers are never good, but this time they’re worse than ever, with more than 6,500 people—nearly 18 per day—struck and killed while walking in 2020.

While news coverage of these deaths would have you believe they’re a tragic consequence of someone getting behind the wheel drunk, or looking at their phone, or even wearing dark clothing or headphones, the report argues the real culprit is street design that prioritizes speed and volume over safety and cost.

Using this principle as a guide, the report authors lay out their findings, as well as recommendations for the kind of changes agencies, municipalities, and residents can make to counter the rising rate of pedestrian deaths. Here is our summary.

The pandemic made an already bad situation worse

One of the most obvious changes during the early stages of the pandemic was a dramatic decline in vehicle traffic. Although you might expect a decline in traffic deaths to accompany such a shift, the exact opposite occurred: deaths increased as people took advantage of open roads to speed and drive recklessly. “It was incredibly ironic,” report authors note. “Congestion, something transportation agencies spend billions to eliminate, seems to have been slowing traffic and reducing deadly crashes.”

Deaths increased most in cities that were already the most unsafe for walkers

While vehicle trips during the pandemic went down, walking trips increased in every state and metro area analyzed in the report. In places where walking was common before the pandemic, death rates decreased or increased only slightly during the pandemic. But in places where walking was less common pre-pandemic, where streets are not designed to accommodate pedestrians, deaths rose dramatically. “This underscores the fact that these tragedies are preventable,” according to report authors. “More walking does not have to equal more deaths, if streets are designed with safety as the top priority.”

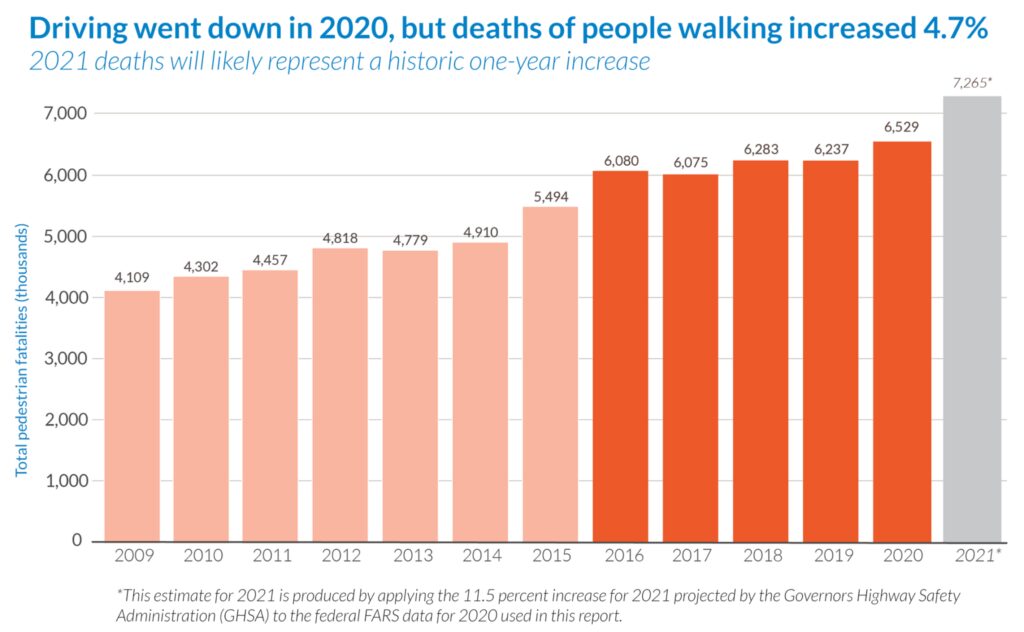

People of color, low-income residents, and older adults are much more likely to die while walking

Although no demographic is excluded from the harms of traffic violence, certain populations are disproportionately represented. These include people of color, particularly Black and Native Americans, who are more than twice as likely to die while walking compared to White, Non-Hispanic Americans. A big part of this has to do with the way road networks were developed in the U.S. post-1960, with wide, high-speed roads cutting through Black, Brown, and low-income neighborhoods, often with few if any safety features put in place.

Arterial roads are by far the most dangerous street type

Considering how vast America’s road network is, the challenge of making it less deadly to pedestrians can seem impossible. But if you look at where the most dangerous roads are in a given metro area, you’ll no doubt find the majority are “arterials”—wide, fast-moving roads that funnel vehicle traffic to and from sites like housing subdivisions and shopping centers. Arterials make up just 15% of all urban roads in the U.S. but are where 67% of pedestrian deaths occur. Knowing this makes the work of identifying locations for safety improvements more manageable, and helps departments ensure limited resources are well-spent.

Agencies have more tools, resources, and flexibility than ever to build safer streets

Despite the discouraging statistics, the report also offers reason for optimism. One key change: the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, which not only offers new funding for pedestrian safety projects but expands the street design guidelines cities are allowed to adopt, such as those from the National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO). Cities can and should adopt their own requirements for safe, human-centered street design, and demand that states channel funding away from traditional, car-centric initiatives toward multimodal safety-related projects.